- US Legal Forms

- Commercial

-

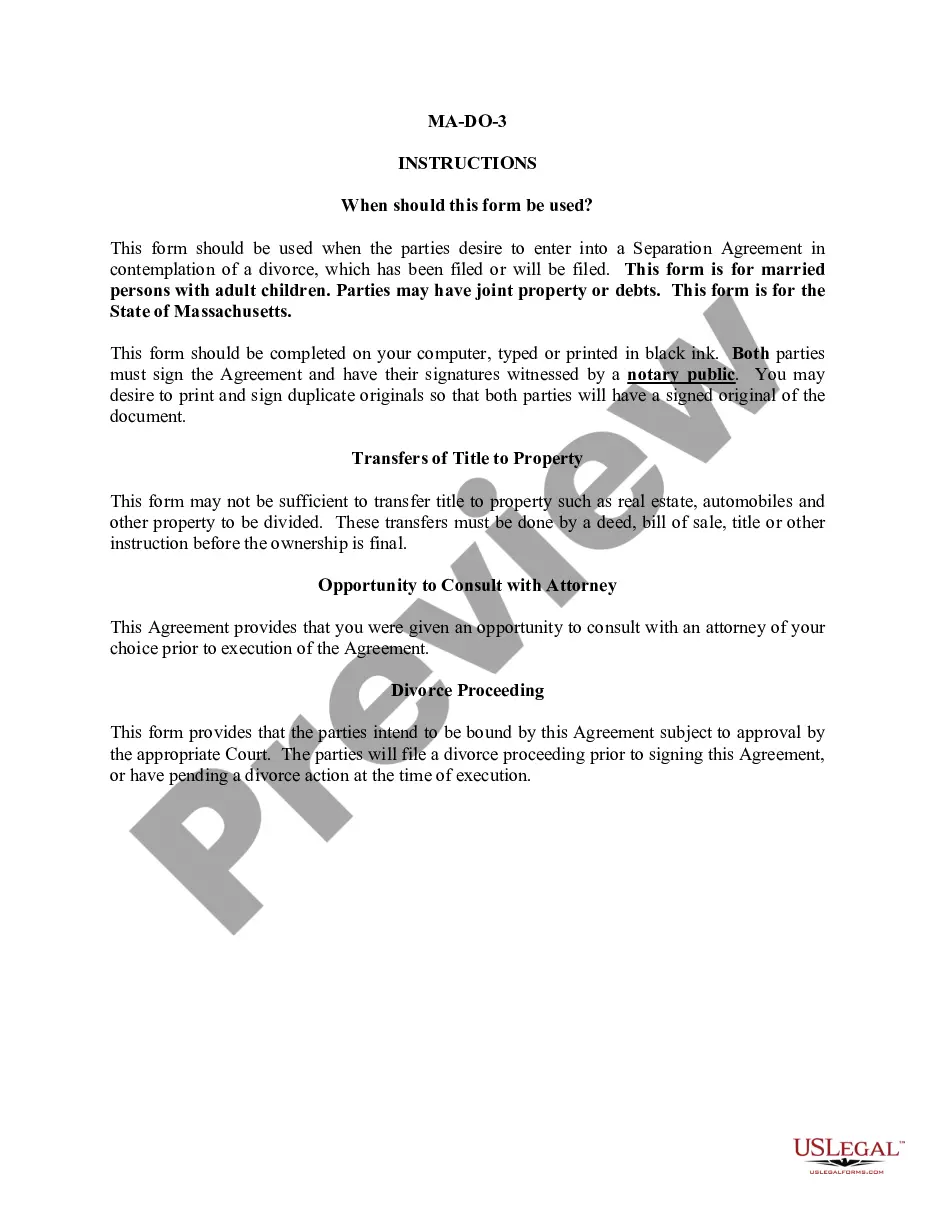

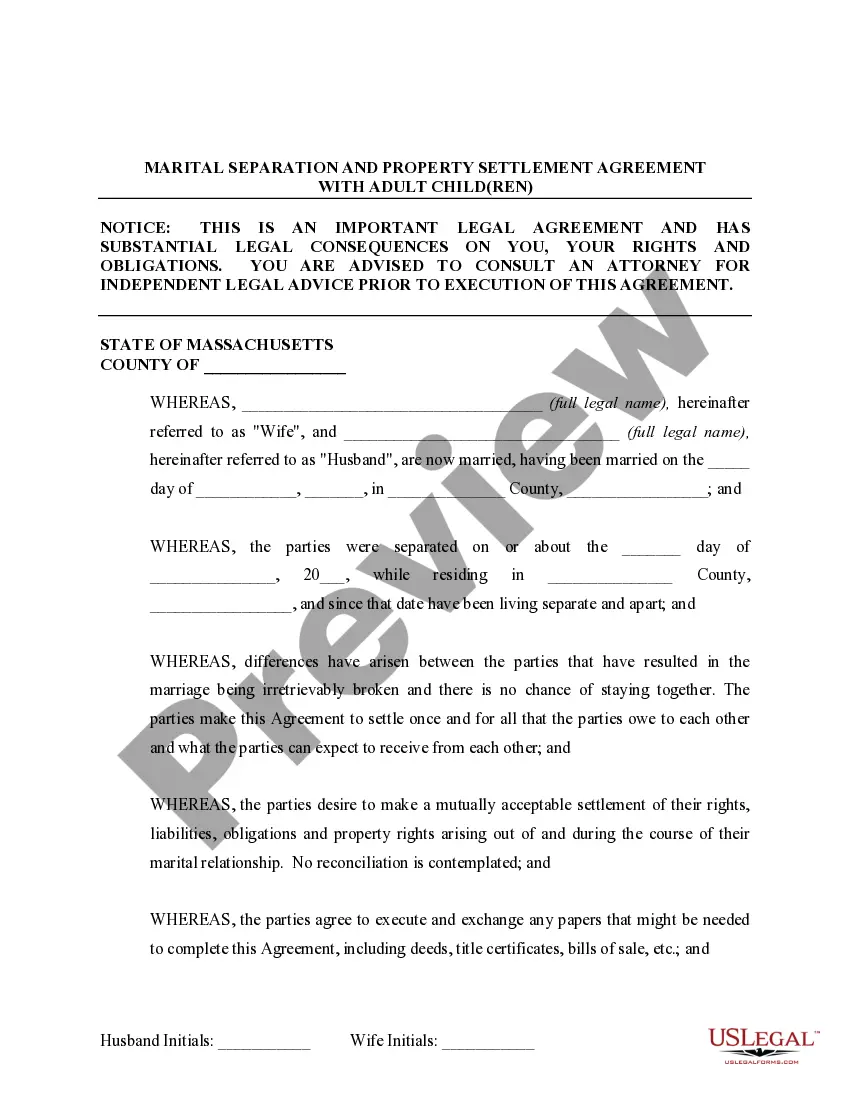

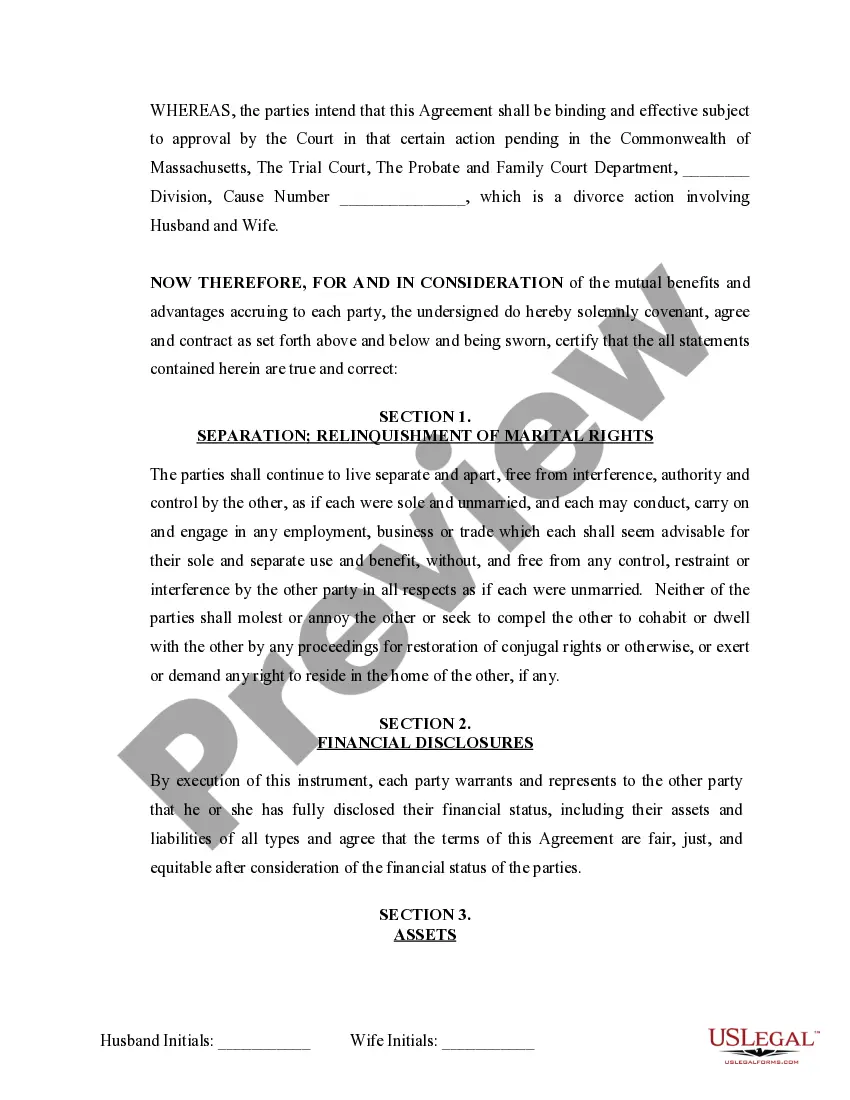

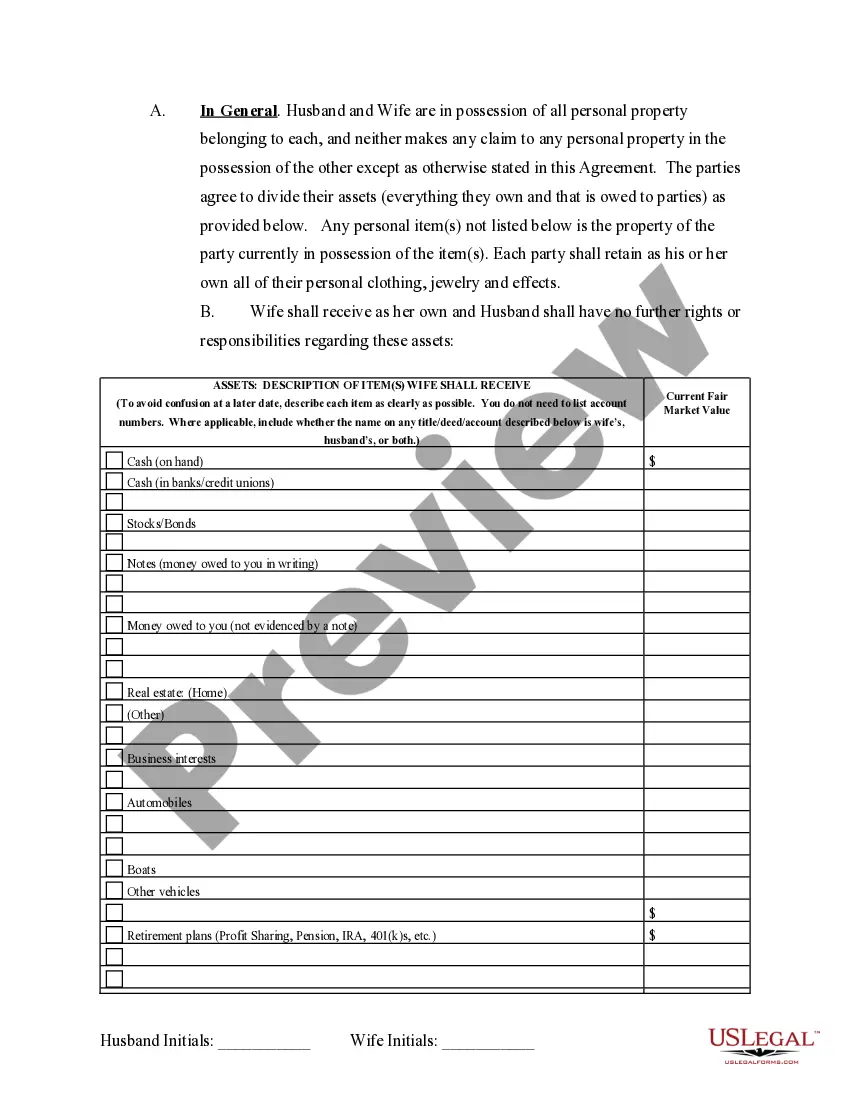

Massachusetts Marital Domestic Separation and Property Settlement...

Massachusetts Property To Rent

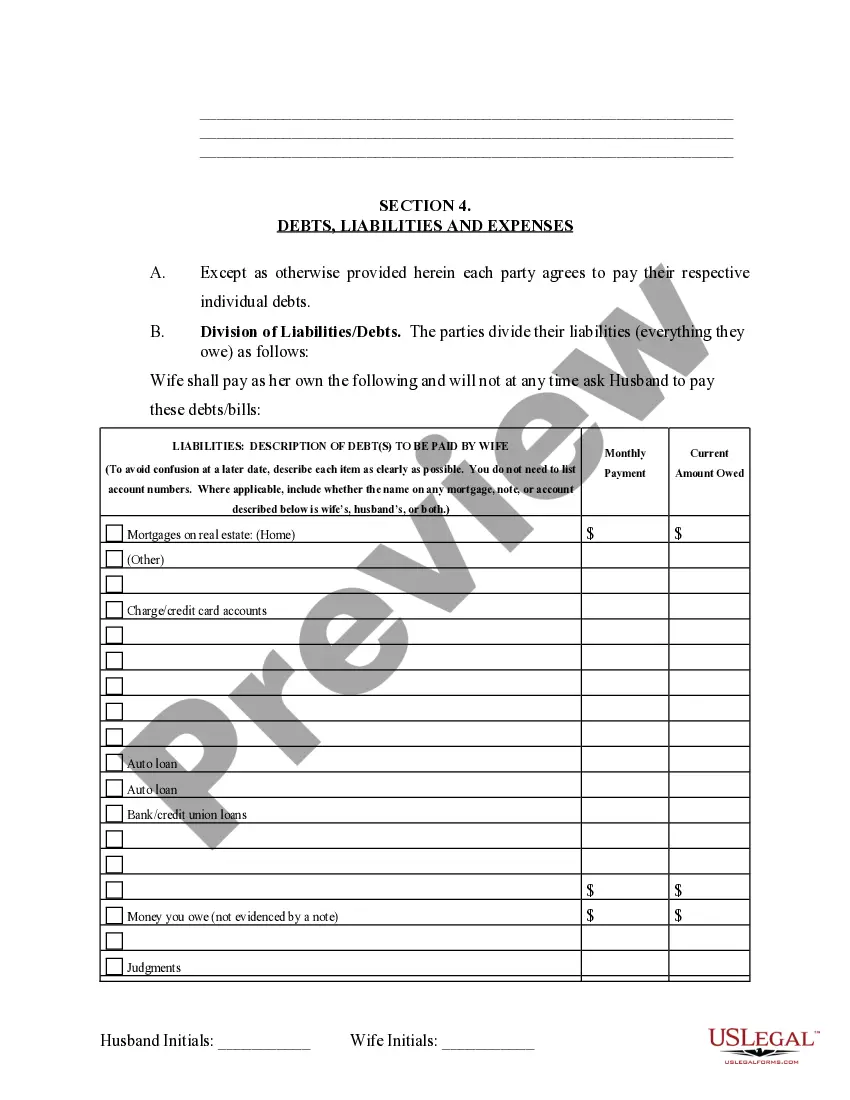

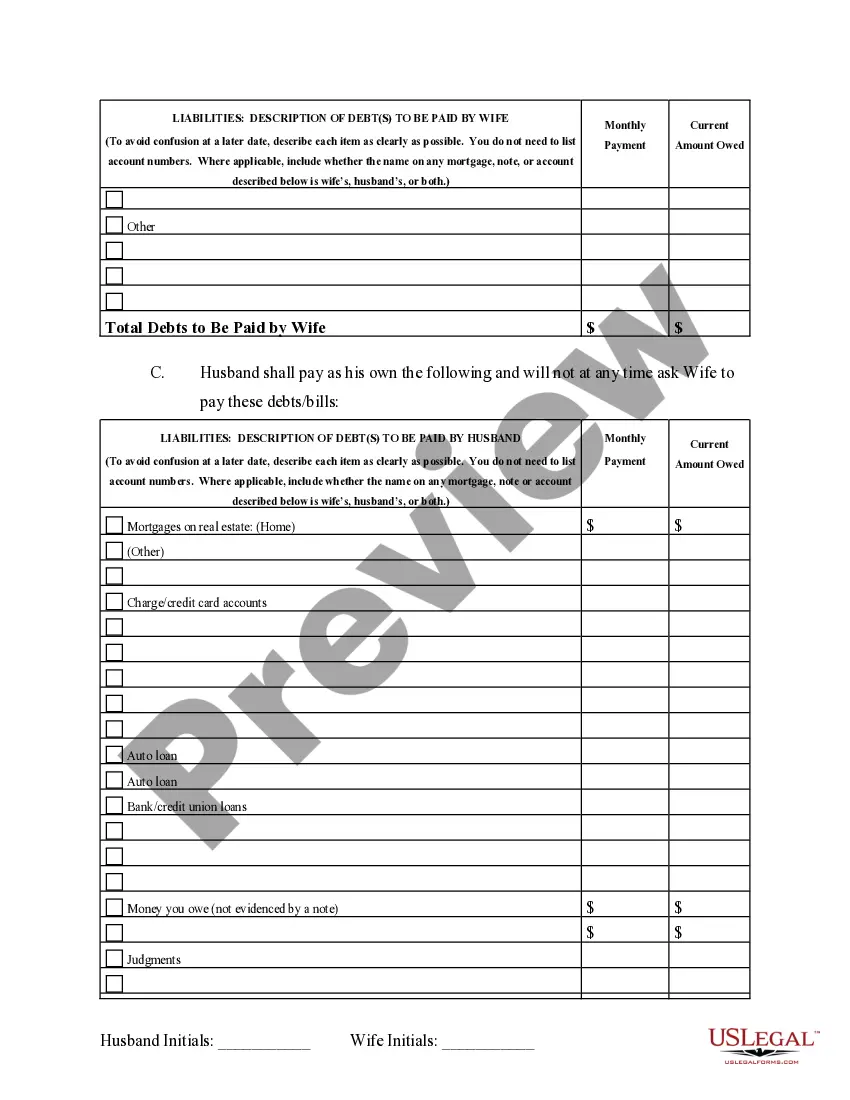

Description Settlement Debts

Agreement Divorce Form Related forms

View Sample letter asking for political support with a project

View Sample letter asking for political support with money

View Sample letter asking for political support with housing

View Sample letter asking for political support with immigration

View Sample letter asking for political support with green card

Related legal definitions

Viewed forms

Separation Agreement Form Rating

Marital Agreement Divorce Form popularity

Marital Divorce Form Other Form Names

Massachusetts Property To Rent Related Searches

-

cheap houses for rent in massachusetts

-

farm houses for rent in massachusetts

-

homes for rent by owner in ma

-

single family homes for rent in massachusetts

-

rent single family house

-

craigslist houses for rent massachusetts

-

3 bedroom house for rent in massachusetts

-

apartments for rent in massachusetts

-

cheap houses for rent in massachusetts

-

farm houses for rent in massachusetts

Property Settlement Interesting Questions

In Massachusetts, rental laws are governed by the state's Tenant-Landlord Law. This law regulates various aspects of renting, including security deposit limits, eviction procedures, and tenant rights.

The cost of renting a property in Massachusetts varies based on several factors such as location, property type, and size. On average, rental prices range from $1,500 to $3,000 per month for apartments, while larger houses can cost upwards of $3,500 per month.

In Massachusetts, landlords are generally not allowed to increase the rent during the lease term unless it is specified in the lease agreement. However, they can increase the rent when renewing or entering into a new lease agreement.

The typical lease term in Massachusetts is one year. However, landlords and tenants can negotiate different lease durations based on their mutual agreement.

In Massachusetts, a landlord can ask for a security deposit equal to the first month's rent. The security deposit must be held in a separate, interest-bearing account, and the landlord must provide a receipt and an itemized list of damages (if any) within 30 days of the tenant moving out.

If the landlord fails to return the security deposit or provide a proper explanation within 30 days of the tenant moving out, the tenant can take legal action and potentially recover up to three times the withheld amount, plus attorney fees.

In Massachusetts, landlords are required to give proper notice to tenants before entering the rented property. They can only enter for specific reasons, such as making repairs, conducting inspections, or showing the property to potential buyers or tenants.

Tenants in Massachusetts have several rights, including the right to live in a habitable and safe property, protection against unfair eviction, privacy rights, the right to a return of their security deposit, and the right to request repairs from the landlord.

In certain circumstances, Massachusetts tenants have the right to withhold rent if the landlord fails to make necessary repairs that significantly affect the habitability of the property. However, specific procedures and requirements must be followed, such as giving written notice to the landlord and allowing a reasonable time for the repairs to be completed.

No, in Massachusetts, it is illegal for landlords to discriminate against potential tenants based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, or other protected characteristics. Landlords must follow fair housing laws and treat all applicants equally.

Settlement Divorce Trusted and secure by over 3 million people of the world’s leading companies

-

No results found.

-

Massachusetts

-

Alabama

-

Alaska

-

Arizona

-

Arkansas

-

California

-

Colorado

-

Connecticut

-

Delaware

-

District of Columbia

-

Florida

-

Georgia

-

Hawaii

-

Idaho

-

Illinois

-

Indiana

-

Iowa

-

Kansas

-

Kentucky

-

Maine

-

Maryland

-

Michigan

-

Minnesota

-

Mississippi

-

Missouri

-

Montana

-

Nebraska

-

Nevada

-

New Jersey

-

New Mexico

-

New York

-

North Carolina

-

North Dakota

-

Ohio

-

Oklahoma

-

Oregon

-

Pennsylvania

-

Rhode Island

-

South Dakota

-

Tennessee

-

Utah

-

Vermont

-

Virginia

-

Washington

-

West Virginia

-

Wisconsin

-

Wyoming

Note: This summary is not intended to be an all-inclusive discussion of the law of separation agreements in Massachusetts, but does include basic and other provisions.

General Summary: Separation agreements, when free from fraud and coercion and when fair and reasonable, are valid. This is subject to the approval of the the court. If a judge rules, either at the time of the entry of a judgment nisi of divorce or at any subsequent time, that the agreement was not the product of fraud or coercion, that it was fair and reasonable at the time of entry of the judgment nisi, and that the parties clearly agreed on the finality of the agreement on the subject of interspousal support, the agreement concerning interspousal support should be specifically enforced, absent countervailing equities.

The power of a Probate Court to modify its support orders may not be restricted by an agreement between a husband and a wife which purports to fix for all time the amount of the husband's support obligation. This is especially true regarding support provisions under Section 1A of Chapter 208.

Statutes:

PART II.

REAL AND PERSONAL PROPERTY AND DOMESTIC RELATIONS.

TITLE III.

DOMESTIC RELATIONS.

CHAPTER 208.

DIVORCE.

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage; commencement of action; complaint accompanied by statement and dissolution agreement; procedure:

An action for divorce on the ground of an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage may be commenced with the filing of: (a) a petition signed by both joint petitioners or their attorneys; (b) a sworn affidavit that is either jointly or separately executed by the petitioners that an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage exists; and (c) a notarized separation agreement executed by the parties except as hereinafter set forth and no summons or answer shall be required. After a hearing on a separation agreement which has been presented to the court, the court shall, within thirty days of said hearing, make a finding as to whether or not an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage exists and whether or not the agreement has made proper provisions for custody, for support and maintenance, for alimony and for the disposition of marital property, where applicable.

In making its finding, the court shall apply the provisions of section thirty-four, except that the court shall make no inquiry into, nor consider any evidence of the individual marital fault of the parties. In the event the notarized separation agreement has not been filed at the time of the commencement of the action, it shall in any event be filed with the court within ninety days following the commencement of said action.

If the finding is in the affirmative, the court shall approve the agreement and enter a judgment of divorce nisi. The agreement either shall be incorporated and merged into said judgment or by agreement of the parties, it shall be incorporated and not merged, but shall survive and remain as an independent contract. In the event that the court does not approve the agreement as executed, or modified by agreement of the parties, said agreement shall become null and void and of no further effect between the parties; and the action shall be treated as dismissed, but without prejudice. Following approval of an agreement by the court but prior to the entry of judgment nisi, said agreement may be modified in accordance with the foregoing provisions at any time by agreement of the parties and with the approval of the court, or by the court upon the petition of one of the parties after a showing of a substantial change of circumstances; and the agreement, as modified, shall continue as the order of the court.

Thirty days from the time that the court has given its initial approval to a dissolution agreement of the parties which makes proper provisions for custody, support and maintenance, alimony, and for the disposition of marital property, where applicable, notwithstanding subsequent modification of said agreement, a judgment of divorce nisi shall be entered without further action by the parties.

Nothing in the foregoing shall prevent the court, at any time prior to the approval of the agreement by the court, from making temporary orders for custody, support and maintenance, or such other temporary orders as it deems appropriate, including referral of the parties and the children, if any, for marriage or family counseling.

Prior to the entry of judgment under this section, the petition

may be withdrawn by mutual agreement of the parties. Section 1A.

Case Law:

Separation agreements, when free from fraud and coercion and when fair and reasonable, are valid. Reeves v. Reeves, 318 Mass. 381, 384 (1945). If a judge rules, either at the time of the entry of a judgment nisi of divorce or at any subsequent time, that the agreement was not the product of fraud or coercion, that it was fair and reasonable at the time of entry of the judgment nisi, and that the parties clearly agreed on the finality of the agreement on the subject of interspousal support, the agreement concerning interspousal support should be specifically enforced, absent countervailing equities." Knox v. Remick, 371 Mass. 433, (1976).

Decisions have held consistently that the power of a Probate Court

to modify its support orders may not be restricted by an agreement between

a husband and a wife which

purports to fix for all time the amount of the husband's support

obligation. Ryan v. Ryan, 371 Mass. 430, 432 (1976).

The Probate Court has jurisdiction, in appropriate circumstances, to modify

the support provisions of judgments of divorce entered under G.L.c. 208,

§ 1A. Stansel v. Stansel, 385 Mass. 510 (1982) 432 N.E.2d

691. In enacting G.L.c. 208, § 1A, the Legislature did not intend

to use the term "merged" in its technical sense. This is clearly

demonstrated by the phrase which follows that term in the statute. If a

separation agreement approved by the court and incorporated into an order

for judgment were truly to be merged into that order, the separation agreement

could not, "by agreement of the parties . . . also remain as an independent

contract." Stansel v. Stansel, 385 Mass. 510 (1982)

432 N.E.2d 691.

The party seeking a modification of a judgment of divorce normally must demonstrate "a material change of circumstances since the entry of the earlier judgment." Schuler v. Schuler, 382 Mass. 366, 368 (1981). Where, however, the parties have entered into a separation agreement that was fair and reasonable when the judgment of divorce entered, was not the product of fraud or coercion, and survives the judgment of divorce, something more than a "material change of circumstances" must be shown before a judge of the Probate Court is justified in refusing specific enforcement of that agreement.

This court has noted two possible grounds on which a judge reasonably might rely in refusing specific performance of a properly pleaded separation agreement: that the spouse seeking the modification is or will become a public charge, or that the party raising the separation agreement as a bar has not complied with the provisions of that agreement. Osborne v. Osborne, 384 Mass. 591, 599 (1981). The two grounds above are perhaps not the only grounds on which a probate judge may base a refusal to specifically enforce a separation agreement in a modification proceeding. Only in extreme circumstances should a litigant who has properly raised a separation agreement as a bar to Probate Court modification proceedings be forced to bring a separate suit in another forum in order to vindicate his rights under that agreement.

The existence of an independent, enforceable agreement does not

deprive the Probate

Court of jurisdiction to modify its own judgment. The requirement

that Probate Court give full effect to intention of parties as expressed

in separation agreement does

not limit court's power to modify subsequent divorce decrees. Ryan

v. Ryan, 371 Mass. 430, 432 (1976). A surviving agreement

may prompt a judge "in his discretion" not to modify an order, Knox

v. Remick, 371 Mass. 433, 435 (1976); it is not a jurisdictional bar

to the action.

Note: This summary is not intended to be an all-inclusive discussion of the law of separation agreements in Massachusetts, but does include basic and other provisions.

General Summary: Separation agreements, when free from fraud and coercion and when fair and reasonable, are valid. This is subject to the approval of the the court. If a judge rules, either at the time of the entry of a judgment nisi of divorce or at any subsequent time, that the agreement was not the product of fraud or coercion, that it was fair and reasonable at the time of entry of the judgment nisi, and that the parties clearly agreed on the finality of the agreement on the subject of interspousal support, the agreement concerning interspousal support should be specifically enforced, absent countervailing equities.

The power of a Probate Court to modify its support orders may not be restricted by an agreement between a husband and a wife which purports to fix for all time the amount of the husband's support obligation. This is especially true regarding support provisions under Section 1A of Chapter 208.

Statutes:

PART II.

REAL AND PERSONAL PROPERTY AND DOMESTIC RELATIONS.

TITLE III.

DOMESTIC RELATIONS.

CHAPTER 208.

DIVORCE.

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage; commencement of action; complaint accompanied by statement and dissolution agreement; procedure:

An action for divorce on the ground of an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage may be commenced with the filing of: (a) a petition signed by both joint petitioners or their attorneys; (b) a sworn affidavit that is either jointly or separately executed by the petitioners that an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage exists; and (c) a notarized separation agreement executed by the parties except as hereinafter set forth and no summons or answer shall be required. After a hearing on a separation agreement which has been presented to the court, the court shall, within thirty days of said hearing, make a finding as to whether or not an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage exists and whether or not the agreement has made proper provisions for custody, for support and maintenance, for alimony and for the disposition of marital property, where applicable.

In making its finding, the court shall apply the provisions of section thirty-four, except that the court shall make no inquiry into, nor consider any evidence of the individual marital fault of the parties. In the event the notarized separation agreement has not been filed at the time of the commencement of the action, it shall in any event be filed with the court within ninety days following the commencement of said action.

If the finding is in the affirmative, the court shall approve the agreement and enter a judgment of divorce nisi. The agreement either shall be incorporated and merged into said judgment or by agreement of the parties, it shall be incorporated and not merged, but shall survive and remain as an independent contract. In the event that the court does not approve the agreement as executed, or modified by agreement of the parties, said agreement shall become null and void and of no further effect between the parties; and the action shall be treated as dismissed, but without prejudice. Following approval of an agreement by the court but prior to the entry of judgment nisi, said agreement may be modified in accordance with the foregoing provisions at any time by agreement of the parties and with the approval of the court, or by the court upon the petition of one of the parties after a showing of a substantial change of circumstances; and the agreement, as modified, shall continue as the order of the court.

Thirty days from the time that the court has given its initial approval to a dissolution agreement of the parties which makes proper provisions for custody, support and maintenance, alimony, and for the disposition of marital property, where applicable, notwithstanding subsequent modification of said agreement, a judgment of divorce nisi shall be entered without further action by the parties.

Nothing in the foregoing shall prevent the court, at any time prior to the approval of the agreement by the court, from making temporary orders for custody, support and maintenance, or such other temporary orders as it deems appropriate, including referral of the parties and the children, if any, for marriage or family counseling.

Prior to the entry of judgment under this section, the petition

may be withdrawn by mutual agreement of the parties. Section 1A.

Case Law:

Separation agreements, when free from fraud and coercion and when fair and reasonable, are valid. Reeves v. Reeves, 318 Mass. 381, 384 (1945). If a judge rules, either at the time of the entry of a judgment nisi of divorce or at any subsequent time, that the agreement was not the product of fraud or coercion, that it was fair and reasonable at the time of entry of the judgment nisi, and that the parties clearly agreed on the finality of the agreement on the subject of interspousal support, the agreement concerning interspousal support should be specifically enforced, absent countervailing equities." Knox v. Remick, 371 Mass. 433, (1976).

Decisions have held consistently that the power of a Probate Court

to modify its support orders may not be restricted by an agreement between

a husband and a wife which

purports to fix for all time the amount of the husband's support

obligation. Ryan v. Ryan, 371 Mass. 430, 432 (1976).

The Probate Court has jurisdiction, in appropriate circumstances, to modify

the support provisions of judgments of divorce entered under G.L.c. 208,

§ 1A. Stansel v. Stansel, 385 Mass. 510 (1982) 432 N.E.2d

691. In enacting G.L.c. 208, § 1A, the Legislature did not intend

to use the term "merged" in its technical sense. This is clearly

demonstrated by the phrase which follows that term in the statute. If a

separation agreement approved by the court and incorporated into an order

for judgment were truly to be merged into that order, the separation agreement

could not, "by agreement of the parties . . . also remain as an independent

contract." Stansel v. Stansel, 385 Mass. 510 (1982)

432 N.E.2d 691.

The party seeking a modification of a judgment of divorce normally must demonstrate "a material change of circumstances since the entry of the earlier judgment." Schuler v. Schuler, 382 Mass. 366, 368 (1981). Where, however, the parties have entered into a separation agreement that was fair and reasonable when the judgment of divorce entered, was not the product of fraud or coercion, and survives the judgment of divorce, something more than a "material change of circumstances" must be shown before a judge of the Probate Court is justified in refusing specific enforcement of that agreement.

This court has noted two possible grounds on which a judge reasonably might rely in refusing specific performance of a properly pleaded separation agreement: that the spouse seeking the modification is or will become a public charge, or that the party raising the separation agreement as a bar has not complied with the provisions of that agreement. Osborne v. Osborne, 384 Mass. 591, 599 (1981). The two grounds above are perhaps not the only grounds on which a probate judge may base a refusal to specifically enforce a separation agreement in a modification proceeding. Only in extreme circumstances should a litigant who has properly raised a separation agreement as a bar to Probate Court modification proceedings be forced to bring a separate suit in another forum in order to vindicate his rights under that agreement.

The existence of an independent, enforceable agreement does not

deprive the Probate

Court of jurisdiction to modify its own judgment. The requirement

that Probate Court give full effect to intention of parties as expressed

in separation agreement does

not limit court's power to modify subsequent divorce decrees. Ryan

v. Ryan, 371 Mass. 430, 432 (1976). A surviving agreement

may prompt a judge "in his discretion" not to modify an order, Knox

v. Remick, 371 Mass. 433, 435 (1976); it is not a jurisdictional bar

to the action.