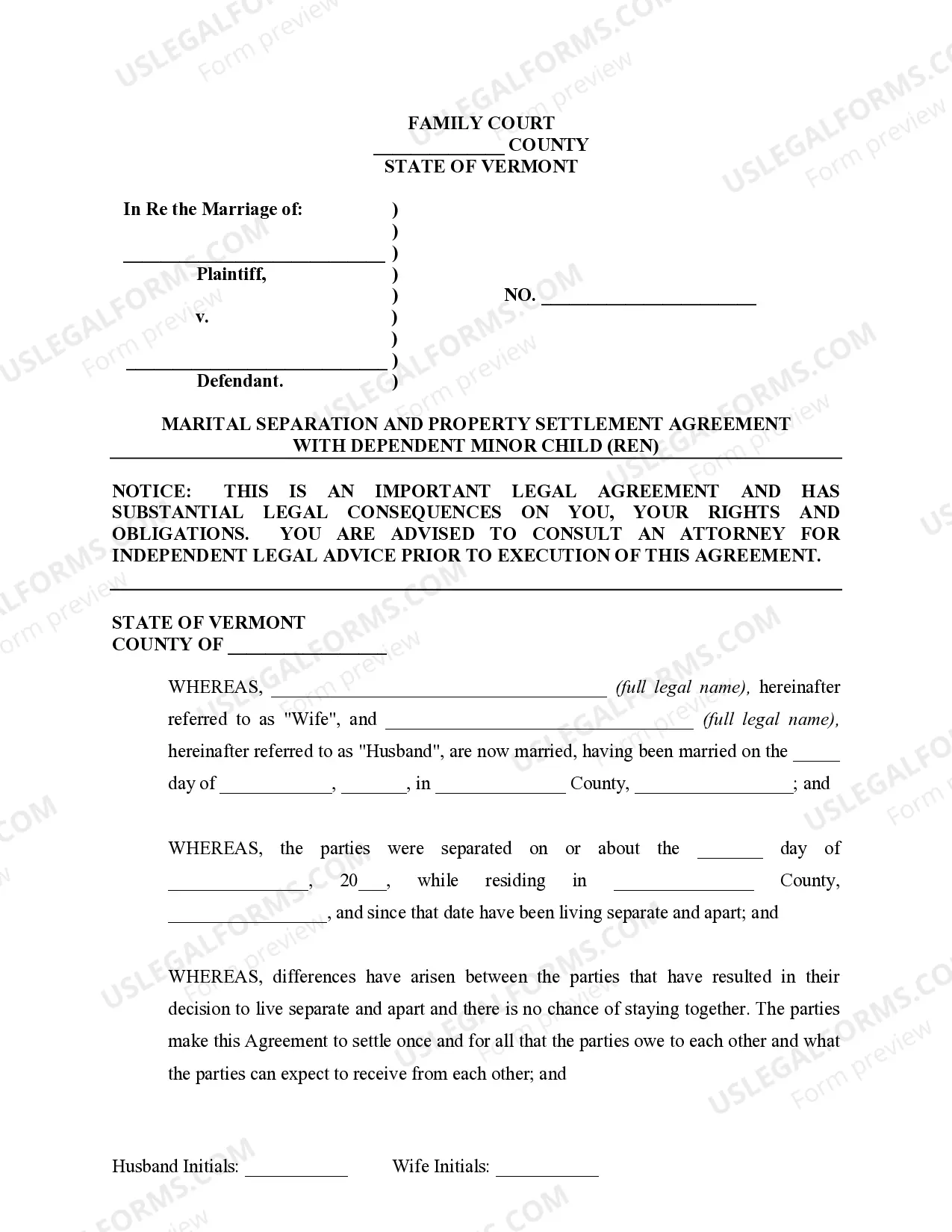

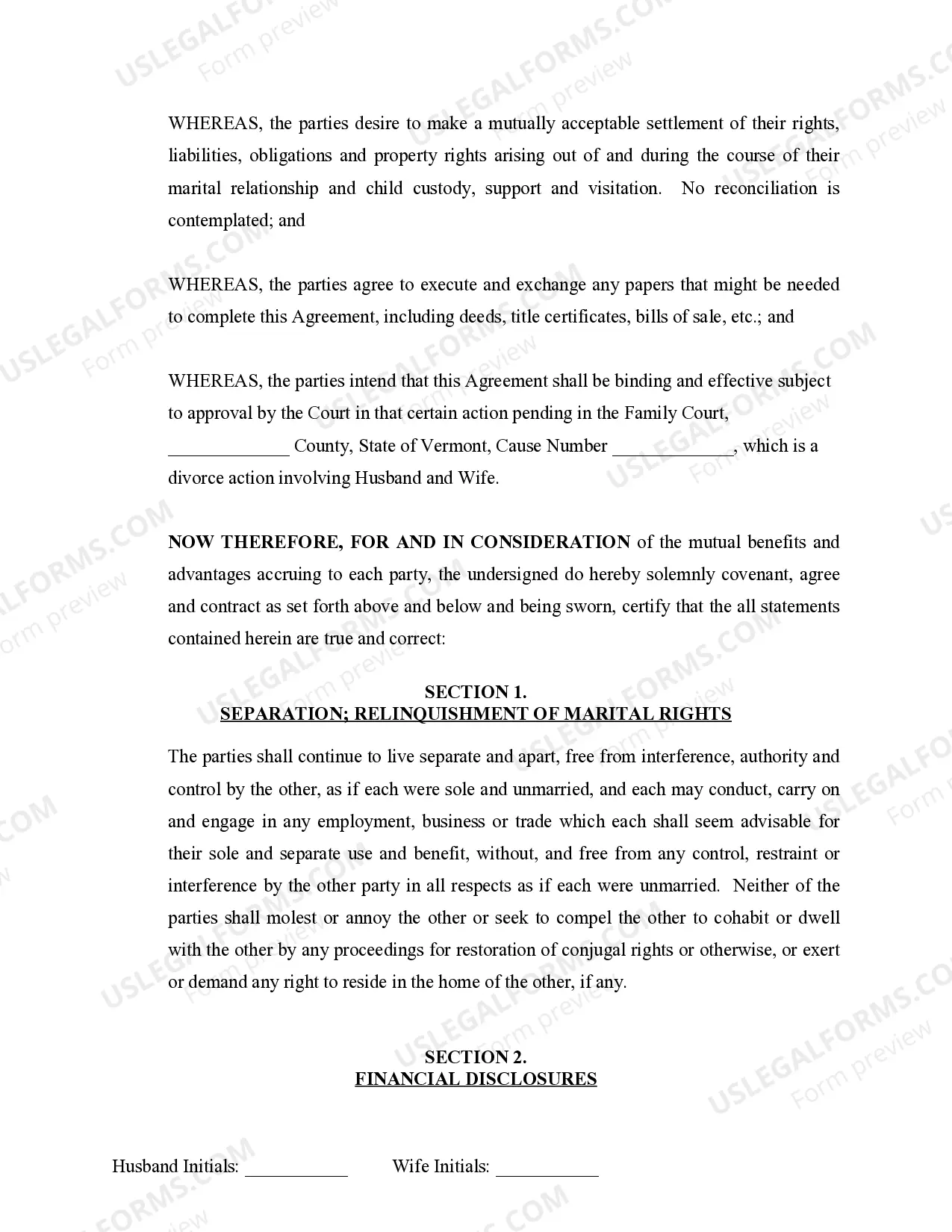

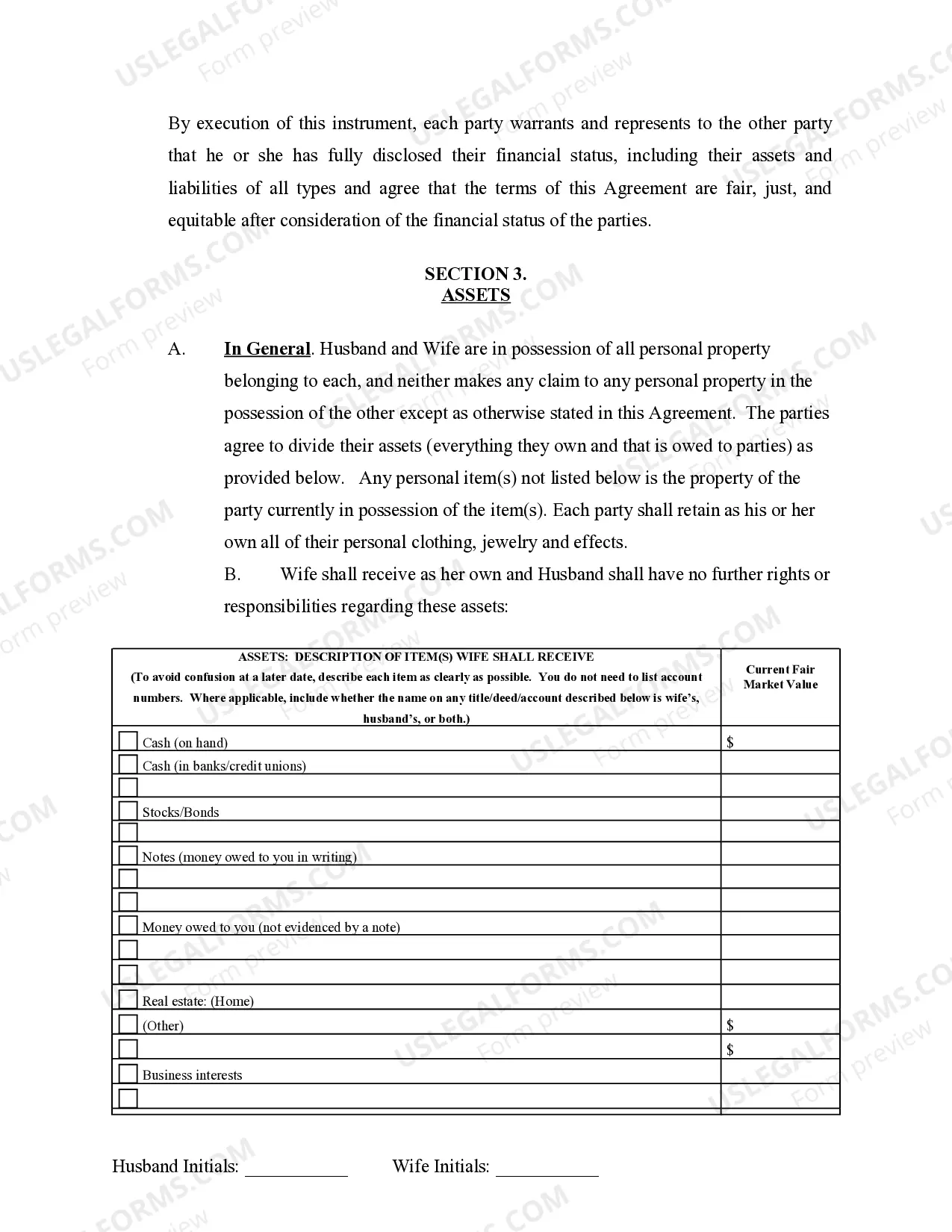

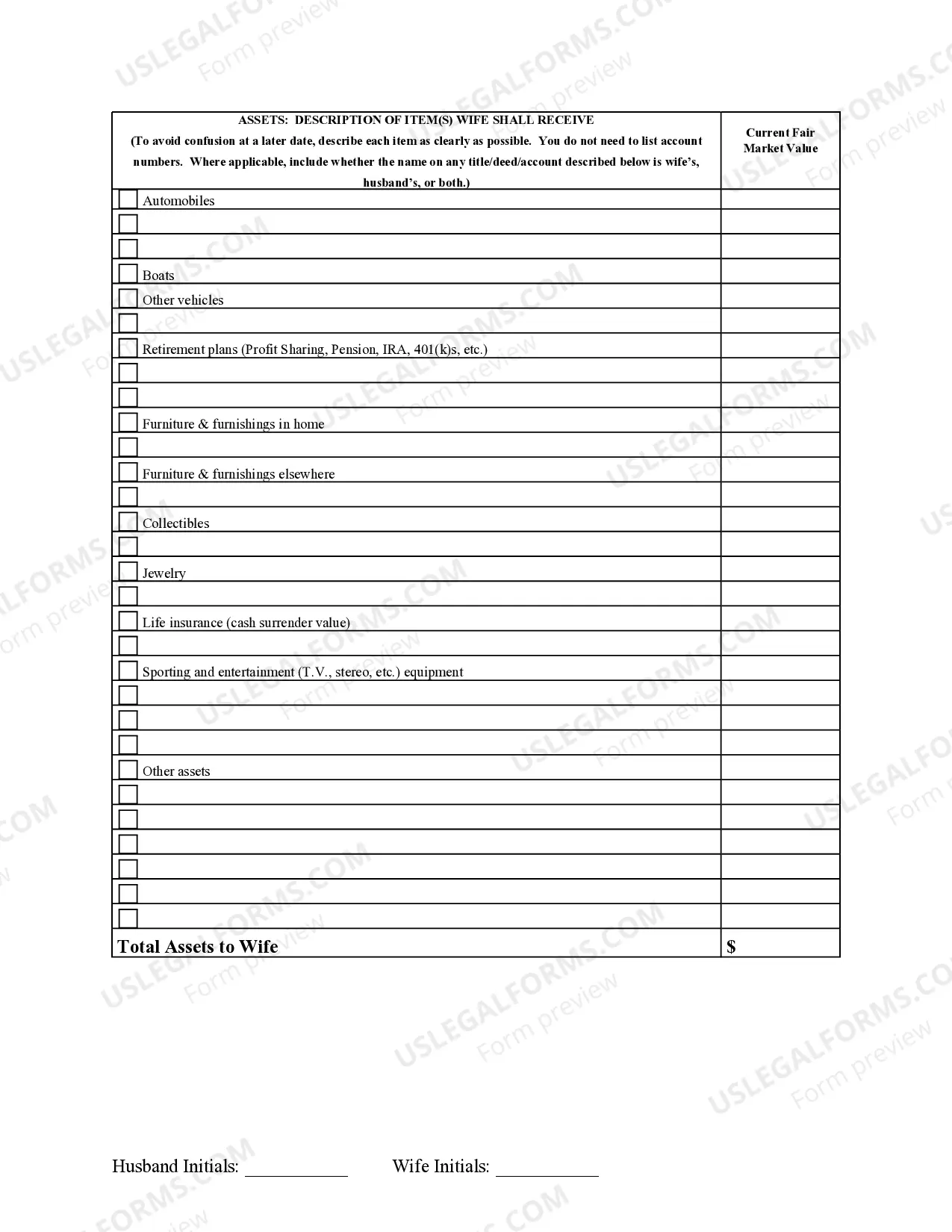

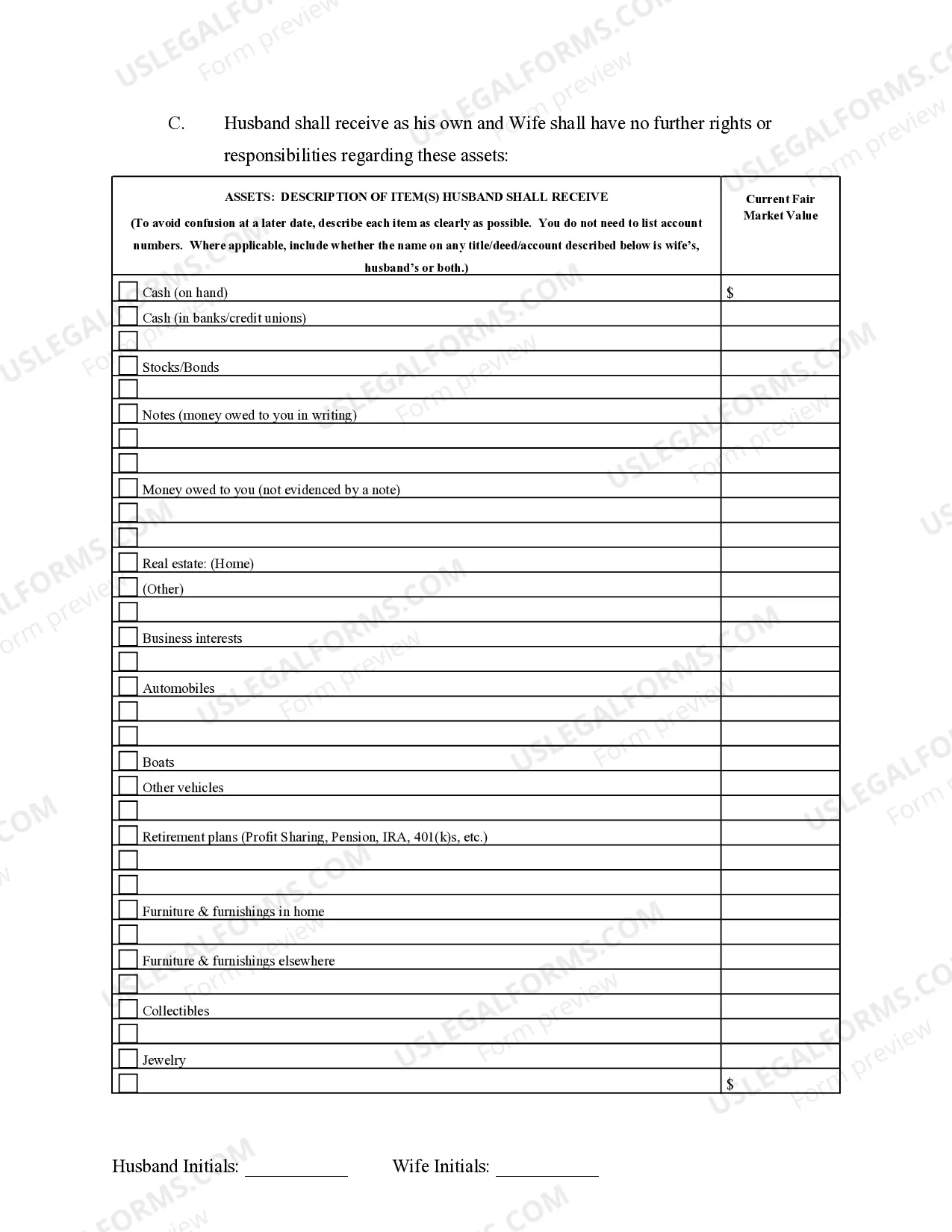

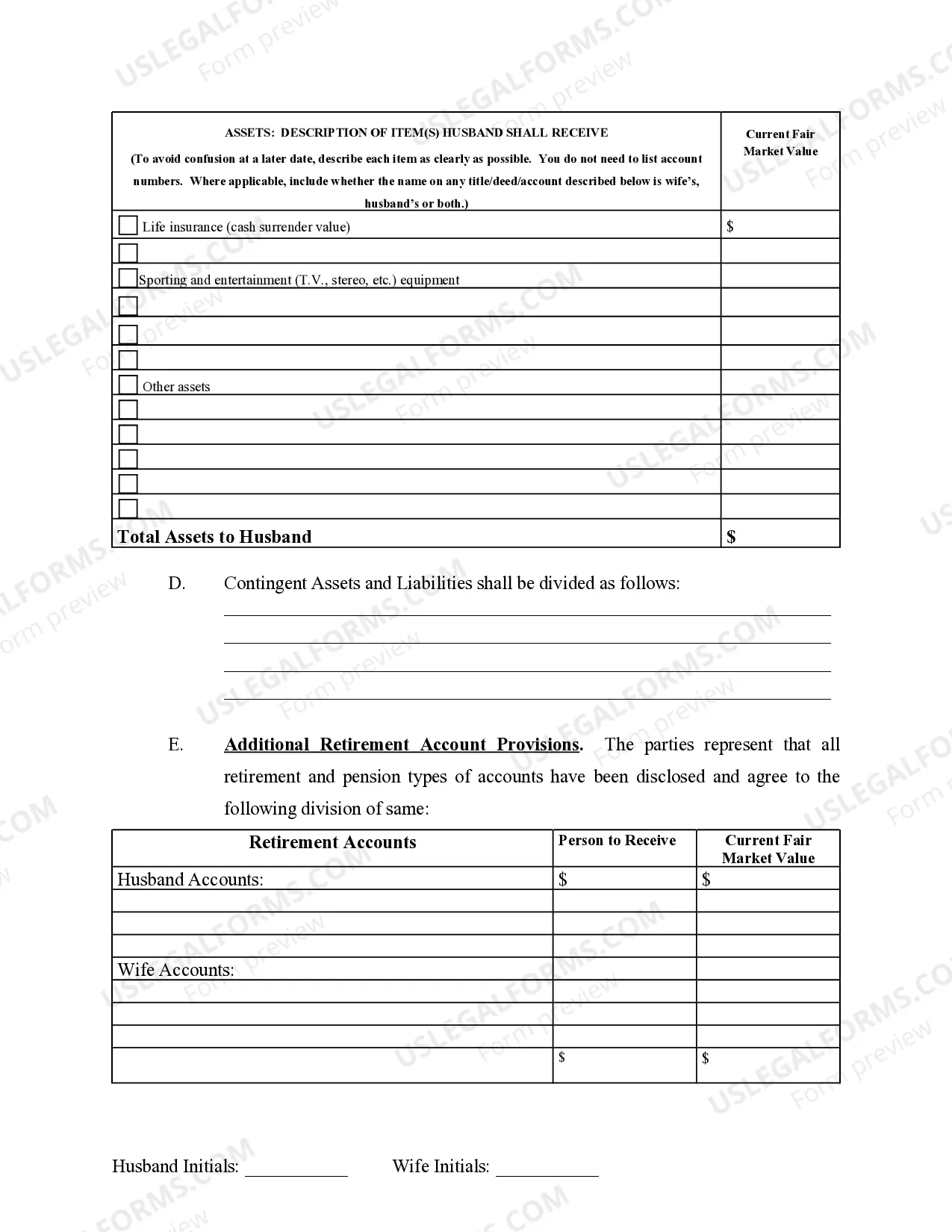

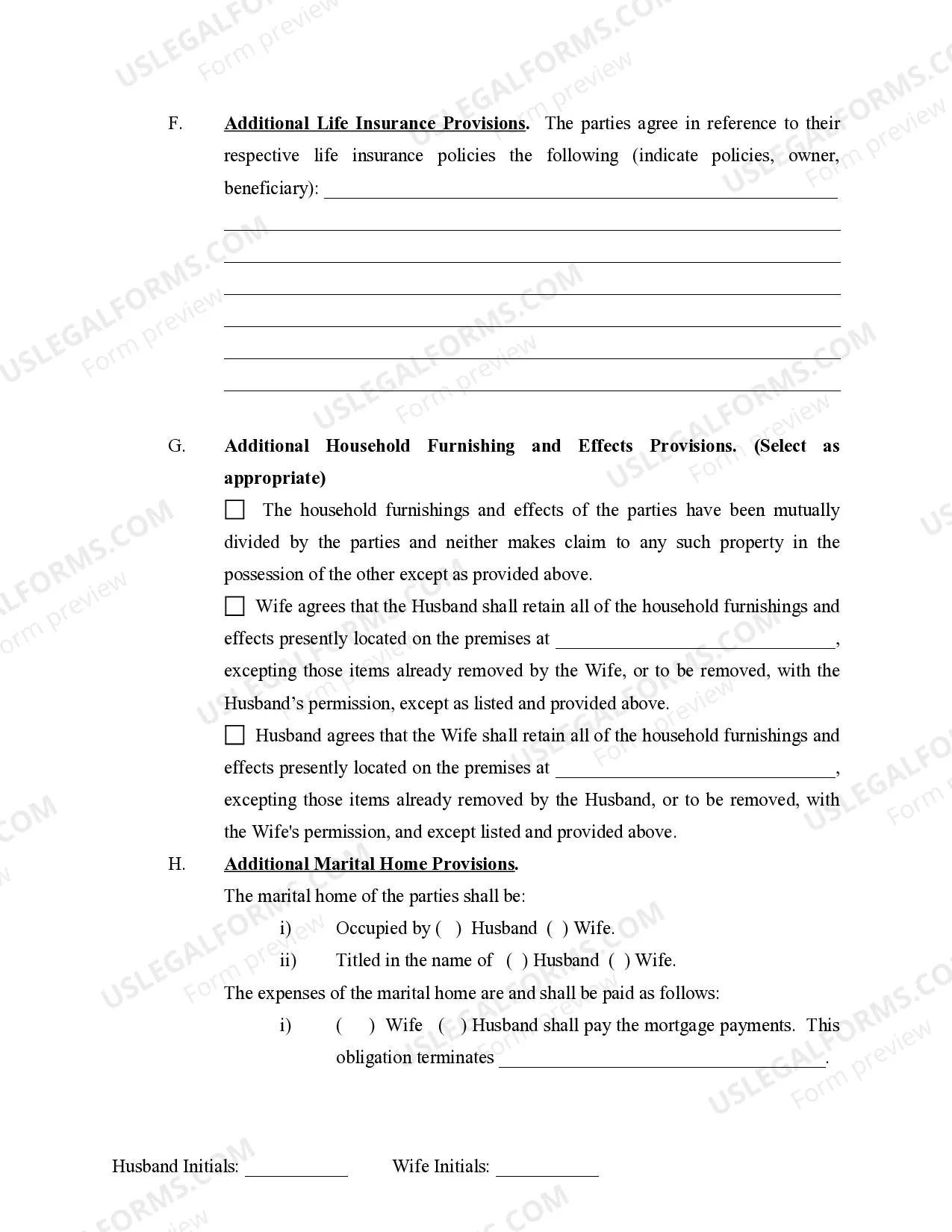

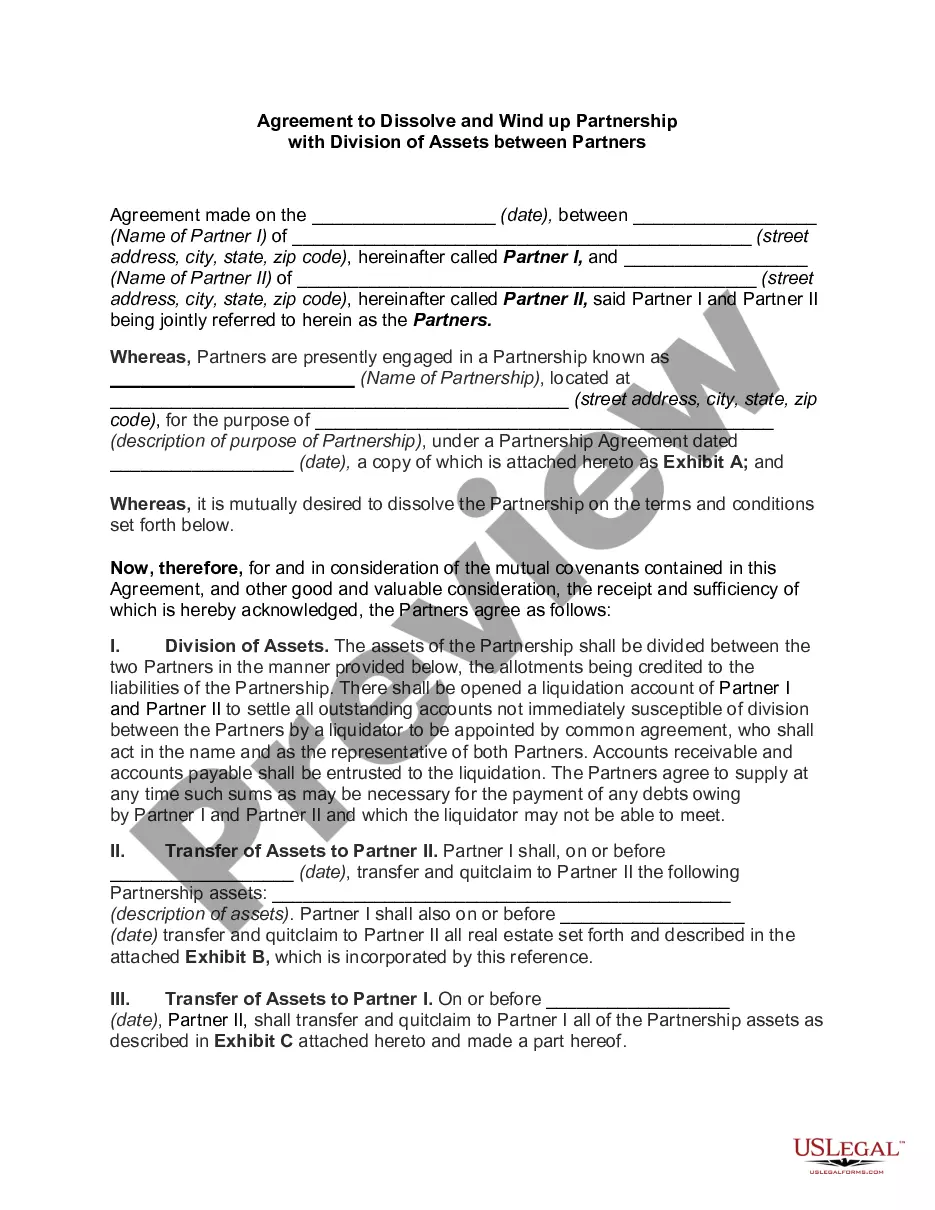

This Marital Domestic Separation and Property Settlement Agreement is a Separation and Property Settlement for persons with minor children. The parties do have joint property and/or debts. This form is for use when a divorce action is pending to resolve all issues. It contains detailed provisions for the division of assets and the payment of liabilities, custody of the children, visitation, child support, etc. It also contains provisions allowing for the payment or non-payment of alimony.

Vermont Marital Domestic Separation and Property Settlement Agreement Minor Children Parties May have Joint Property or Debts where Divorce Action Filed

Description

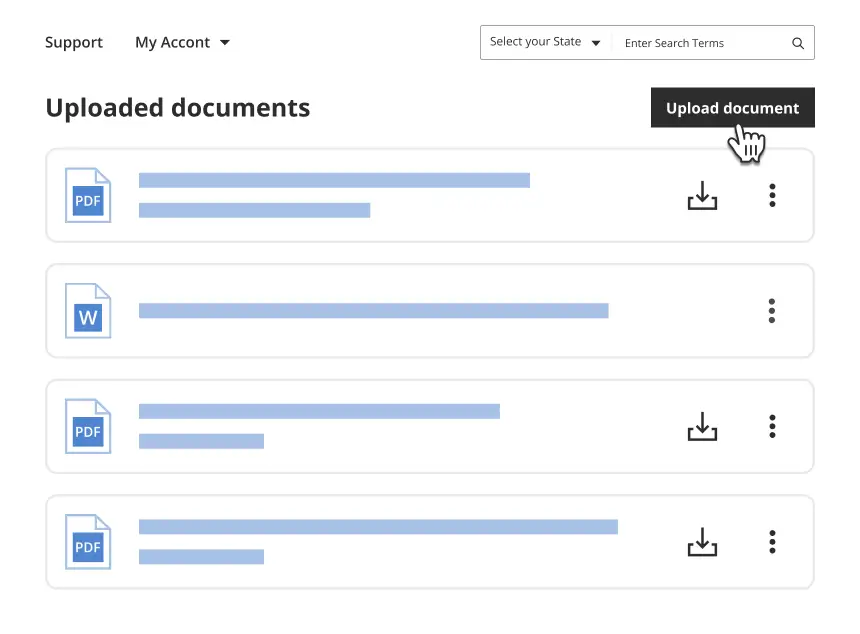

Get your form ready online

Our built-in tools help you complete, sign, share, and store your documents in one place.

Make edits, fill in missing information, and update formatting in US Legal Forms—just like you would in MS Word.

Download a copy, print it, send it by email, or mail it via USPS—whatever works best for your next step.

Sign and collect signatures with our SignNow integration. Send to multiple recipients, set reminders, and more. Go Premium to unlock E-Sign.

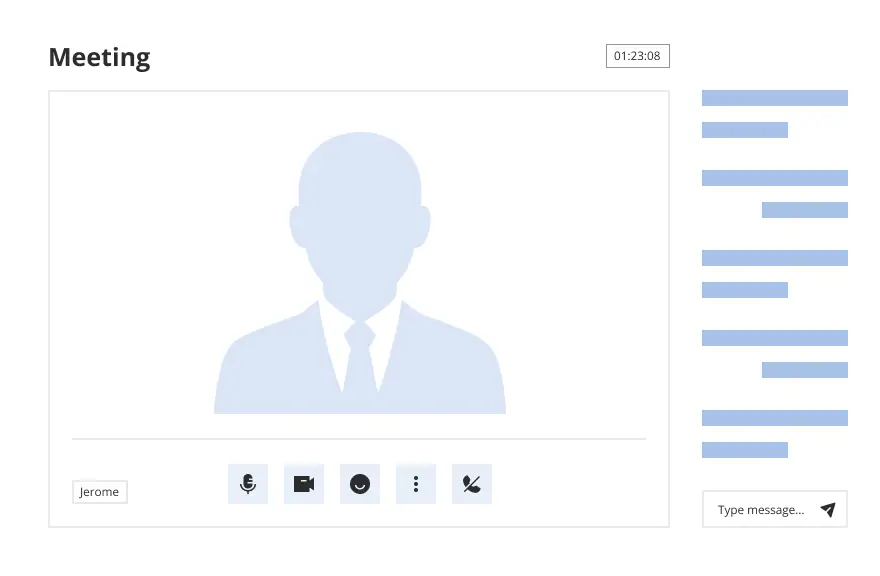

If this form requires notarization, complete it online through a secure video call—no need to meet a notary in person or wait for an appointment.

We protect your documents and personal data by following strict security and privacy standards.

Make edits, fill in missing information, and update formatting in US Legal Forms—just like you would in MS Word.

Download a copy, print it, send it by email, or mail it via USPS—whatever works best for your next step.

Sign and collect signatures with our SignNow integration. Send to multiple recipients, set reminders, and more. Go Premium to unlock E-Sign.

If this form requires notarization, complete it online through a secure video call—no need to meet a notary in person or wait for an appointment.

We protect your documents and personal data by following strict security and privacy standards.

Looking for another form?

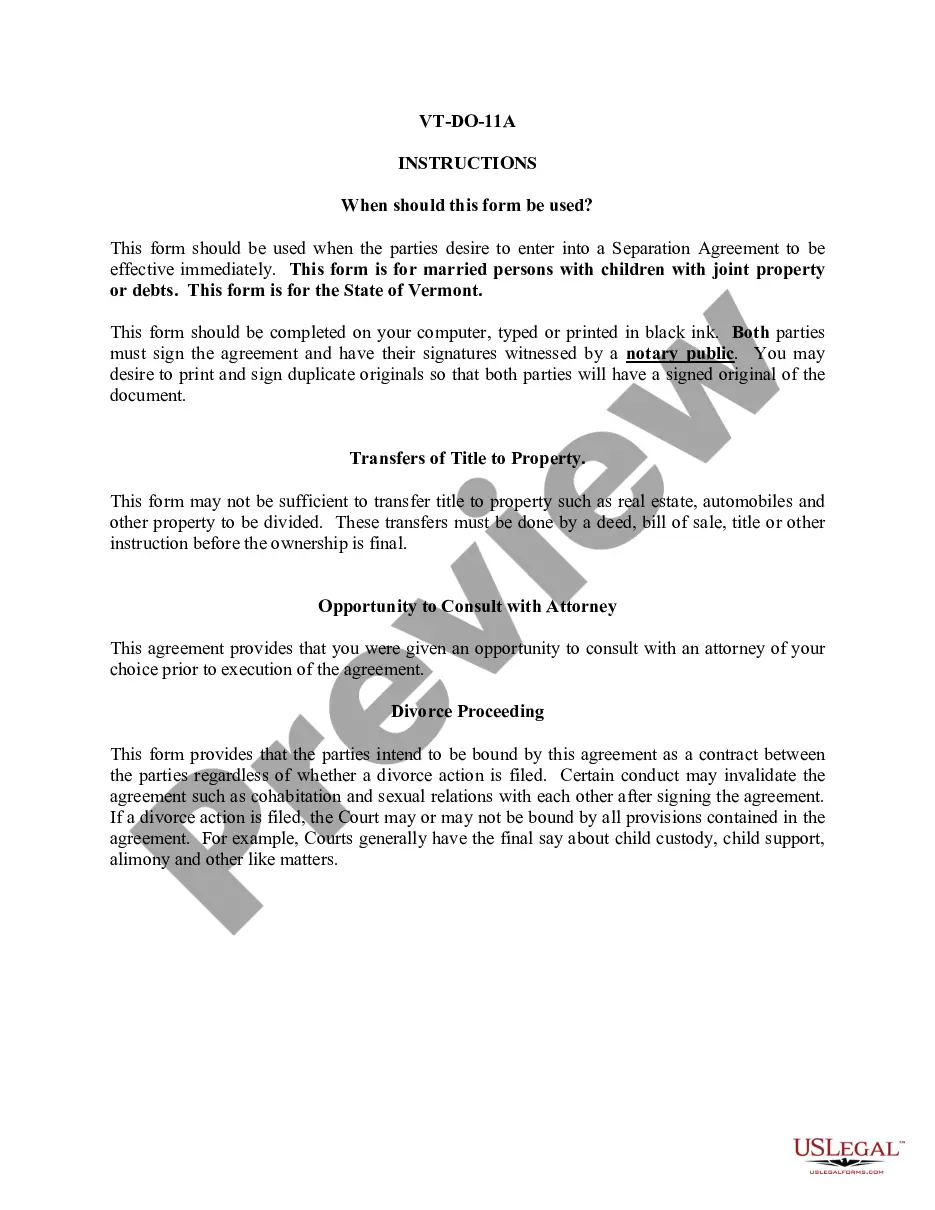

How to fill out Vermont Marital Domestic Separation And Property Settlement Agreement Minor Children Parties May Have Joint Property Or Debts Where Divorce Action Filed?

Searching for a Vermont Marital Domestic Separation and Property Settlement Agreement Minor Children Parties May have Joint Property or Debts where Divorce Action Filed online can be stressful. All too often, you find files that you simply believe are alright to use, but discover later on they are not. US Legal Forms offers over 85,000 state-specific legal and tax forms drafted by professional lawyers in accordance with state requirements. Have any document you are looking for within a few minutes, hassle-free.

If you already have the US Legal Forms subscription, merely log in and download the sample. It’ll automatically be added in in your My Forms section. In case you do not have an account, you must sign-up and pick a subscription plan first.

Follow the step-by-step recommendations listed below to download Vermont Marital Domestic Separation and Property Settlement Agreement Minor Children Parties May have Joint Property or Debts where Divorce Action Filed from the website:

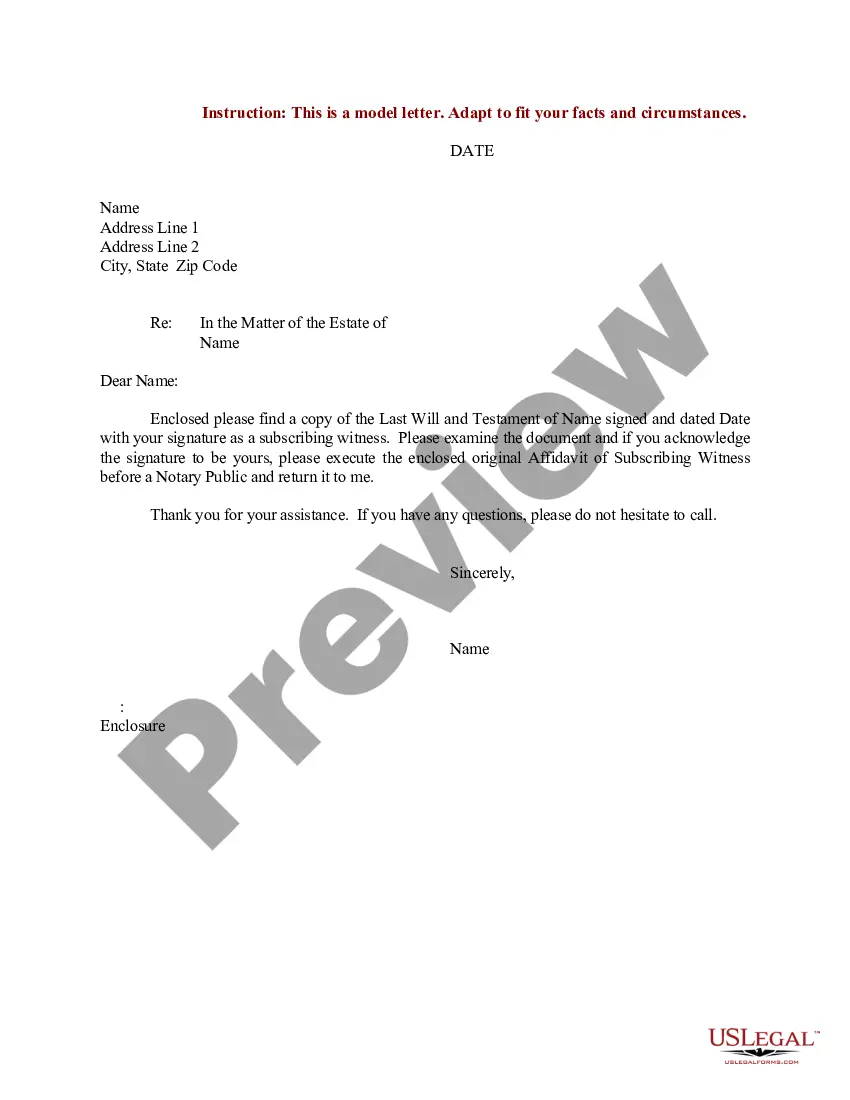

- Read the form description and press Preview (if available) to check if the template meets your requirements or not.

- If the form is not what you need, find others using the Search engine or the listed recommendations.

- If it’s right, click Buy Now.

- Choose a subscription plan and create an account.

- Pay with a card or PayPal and download the document in a preferable format.

- After downloading it, you are able to fill it out, sign and print it.

Obtain access to 85,000 legal forms straight from our US Legal Forms library. In addition to professionally drafted samples, customers may also be supported with step-by-step guidelines regarding how to get, download, and fill out forms.

Form popularity

FAQ

Adultery laws, which make sexual acts illegal if at least one of the parties is married to someone else: Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia and Wisconsin.

Grounds for divorce: Vermont allows a no-fault divorce. That requires that you and your spouse live separate and apart for at least six consecutive months and that you are not likely to get back together.You can't have a final divorce hearing until you've been separated for six months.

Grounds for divorce: Vermont allows a no-fault divorce. That requires that you and your spouse live separate and apart for at least six consecutive months and that you are not likely to get back together.You can't have a final divorce hearing until you've been separated for six months.

In states where fault is required or allowed, adultery can be the reason for your divorce. Proof of adultery may change the amount of child support and alimony a spouse receives. The spouse who was not at fault may also receive more of the household property in the divorce settlement.

You can achieve a legal separation by filing a petition (request) with the court, which allows the judge to divide your marital property, establish child support and alimony, and create a parenting plan for your children.

You, the paramour, can get hit with a lawsuit that could cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars. They're known as "alienation of affection" suits, when an "outsider" interferes in a marriage. The suits are allowed in seven states: Hawaii, Illinois, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Carolina, South Dakota and Utah.

A property settlement is an arrangement made between parties to divide assets, liabilities and financial resources when a couple separate. A property settlement can be made with or without the court's assistance.

Vermont law states that adultery is voluntary sexual intercourse between two people, one of whom is married to someone else.When it comes to divorce, Vermont is a "no-fault" state, which means courts in Vermont do not consider evidence of any marital misconduct, including adultery, when granting a divorce.